With its new group exhibition, Aeroplastics returns to the ironical and directly visual spirit that the gallery has been exploring for many years now. "Humble me" presents a selection of works where each - in its own manner of expression - treats the vast theme of human fragility and isolation. Between romanticism and tragicomedy, they offer an 'off the wall' examination of the place of the individual in our contemporary world, and so throw open the way for debate and argument.

Designer, technician, photographer and filmmaker Arik Levy plays with labels. His project Shine (1996) is very much in this vein: integrated within a series of photographed portraits, the utilitarian object that he has conceived (a lamp) becomes the central element in a stage-setting that transfigures anonymous individuals into so many divine messengers. On the other hand, no need for accessories with the works of Susan Anderson: her young models, prepared at a cost of thousands of dollars for child beauty contests, are already artificial from top to toe. Estimates put at some 100,000 the number of yearly participants under 12 years-of-age taking part in these competitions that reflect the desires, fears and anxieties at play in contemporary American society.

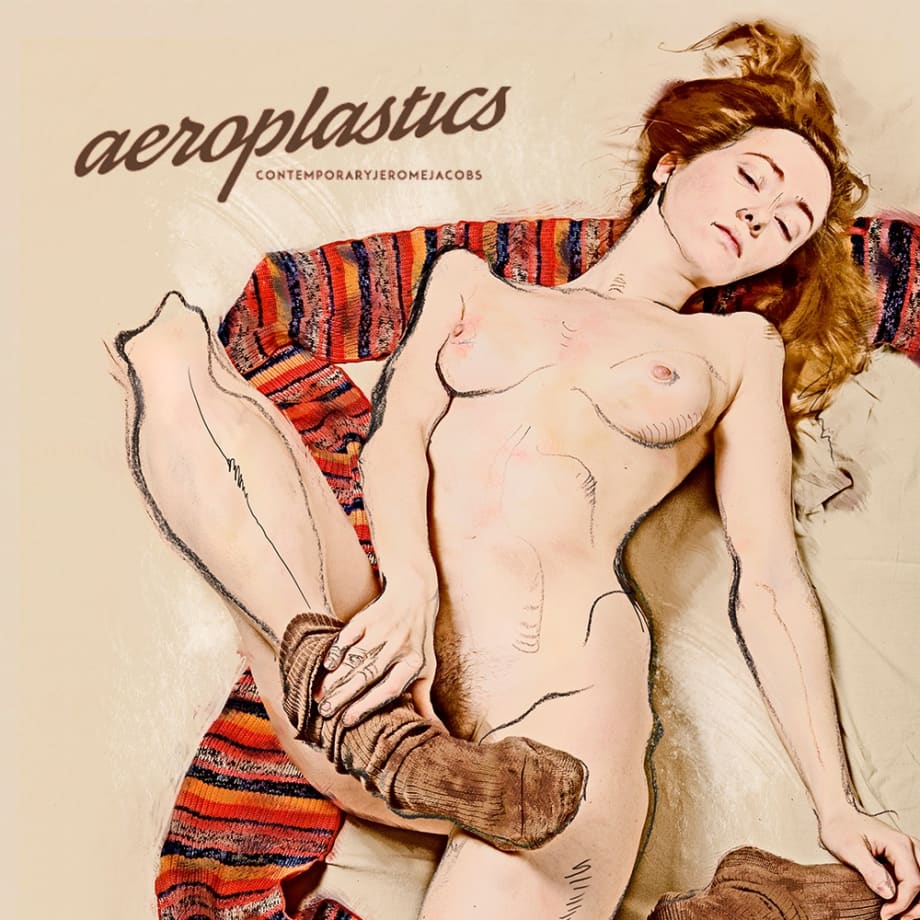

We have a staging of a different sort presented by Carlos & Jason Sanchez in To Control to evoke the manipulation of young minds by Nazi ideology – a process that persists as a tragic actuality today in the context of the Middle East conflict. This reflection is continued with The Everyday, an image that has indeed become 'everyday' in the era of worldwide terrorism, and which testifies to the connection of the Sanchezes with the cinematographic sense of a Jeff Wall. With Teun Hocks, artifice and decor contribute to the absurdist humour of compositions where the artist himself occupies pride of place. He shares with Ellen Kooi a pronounced taste for vast landscapes. With the latter, the mise-en-scène is also the occasion for references to art history, be it with Christina’s World by Andrew Wyeth, or Ophélie by Millais. This concept is developed in a specific way by Katerina Belkina whose self-portraits to which she applies a graphic tint, act as substitutes to the models painted by Degas, Picasso, Modigliani or Gauguin. It is a veritable balancing act that the artist undertakes, mixing photography, digital manipulation, and materials like oils and pencil. She aims to "bring the image to a point where it's able to represent the reality/abstraction duality", all the while not modifying it "beyond reasonable limits". Kate Waters goes about things in a reverse way, starting with photographs, which she subsequently transposes in her paintings. The images she uses are at once strange and banal, reflections of an everyday where anything is now susceptible to becoming subject matter. Terry Rodgers, for his part, transcends the banality of the everyday by selecting models encountered by chance on the street, and then staging them in a way that is at once hyperrealistic and baroque. The artifice of the compositions - if they reinforce the decadent side - equally accentuates the feeling of solitude felt by isolated figures in a world that is not their own. On the other hand, with Marcel Gähler it is the theme of family and happy childhood that rules the roost. His drawings evoke old photographs, but a closer look reveals that these are films projected upon a simple white sheet, like the memory of a memory, suffused with a certain air of melancholia.

The drawings of Filip Markiewicz, as well, evoke images of a recent past, and form part of a vast project from the history of the abbey at Neumünster to Luxembourg – successively treating a place of worship, a hospital and a prison. His Manifesto for the technology of depolitization of the body takes the opposite slant to the concept of the body's politization as put forward by Michel Foucault, and which - pushed to its limits - leads to dictatorships and the holocaust. Ronald Ophuis envisages this tortured and imprisoned body regaining freedom in chaos: his disquieting clowns in striped pyjamas recall the survivors of the extermination camps who, on the long and hard road that led them homewards, would have put on shows as a way of sustaining themselves.

The spectacle offered by Moussa Sarr is his alone, face-to-face with the camera: his sketches play with a grating humour on the politically (in)correct and stereotypes, all the while drawing inspiration from La Fontaine (who will win, the little fly or the horse?). The fable is also in question with Shadi Gadhirian: she incarnates a Miss Butterfly whose life the spider might spare if she brings it insects hiding in the cellar. Rejecting this, the woman/butterfly prefers sacrificing herself by a leap into the web but, touched by this gesture, the spider deigns to let her get away. With Tom Dale as with John Isaacs, it is rather a matter of riddles: their sculptures are all elements of a personal mythology, tragicomic and in perpetual development. Pierrick Sorin manages, as well, to invent a world where he is at once demiurge and victim, like a mad scientist caught in the snare of his own inventions. He shares with Samuel Rousseau an interest in using offbeat animated images. Rousseau's Jardin nomade sets in train a myriad of characters wandering though the maze of an oriental carpet, like in a world ruled by diktat of whatever bent. Those of advertising and intemperate sex, for example, as we are shown in the New York photographs of Wouter Deruytter. Far from this tumult, Bernard Gigounon constructs offbeat universes, silent and deserted from his series "Disharmony", assembling images with no apparent mutual connection – or how from out of chance (dis)harmony may be wrought.

PY Desaive, 2015