Magazin

Publisher: Digital Photo

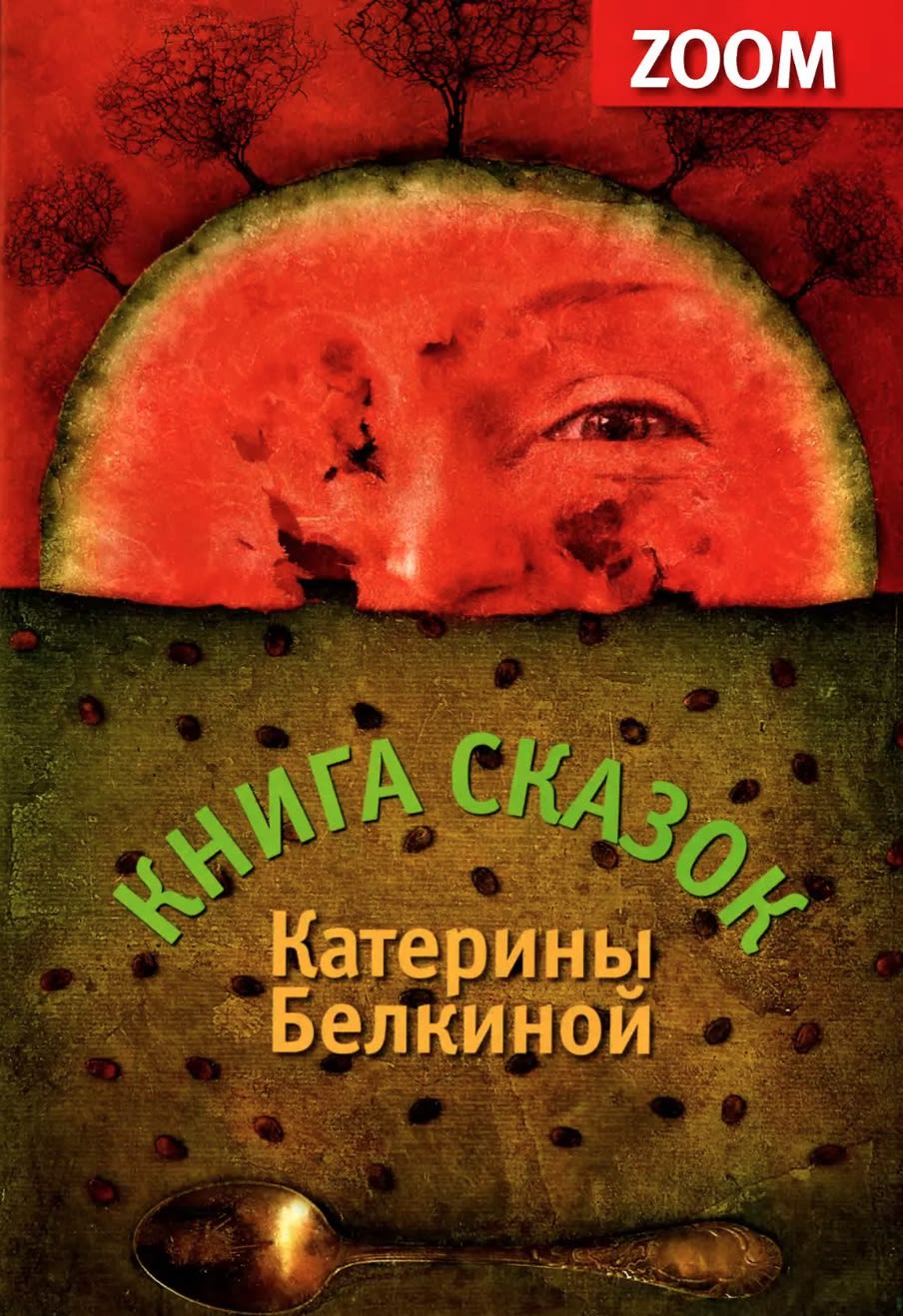

Such people are rare. She loves life as it is but, like no one else, knows how to turn it into a fairytale. She has the ability to feel deeply and joyfully shares her emotions with others. She is a creator, and any work in her hands becomes art—art that has already become a benchmark for many, many artists.

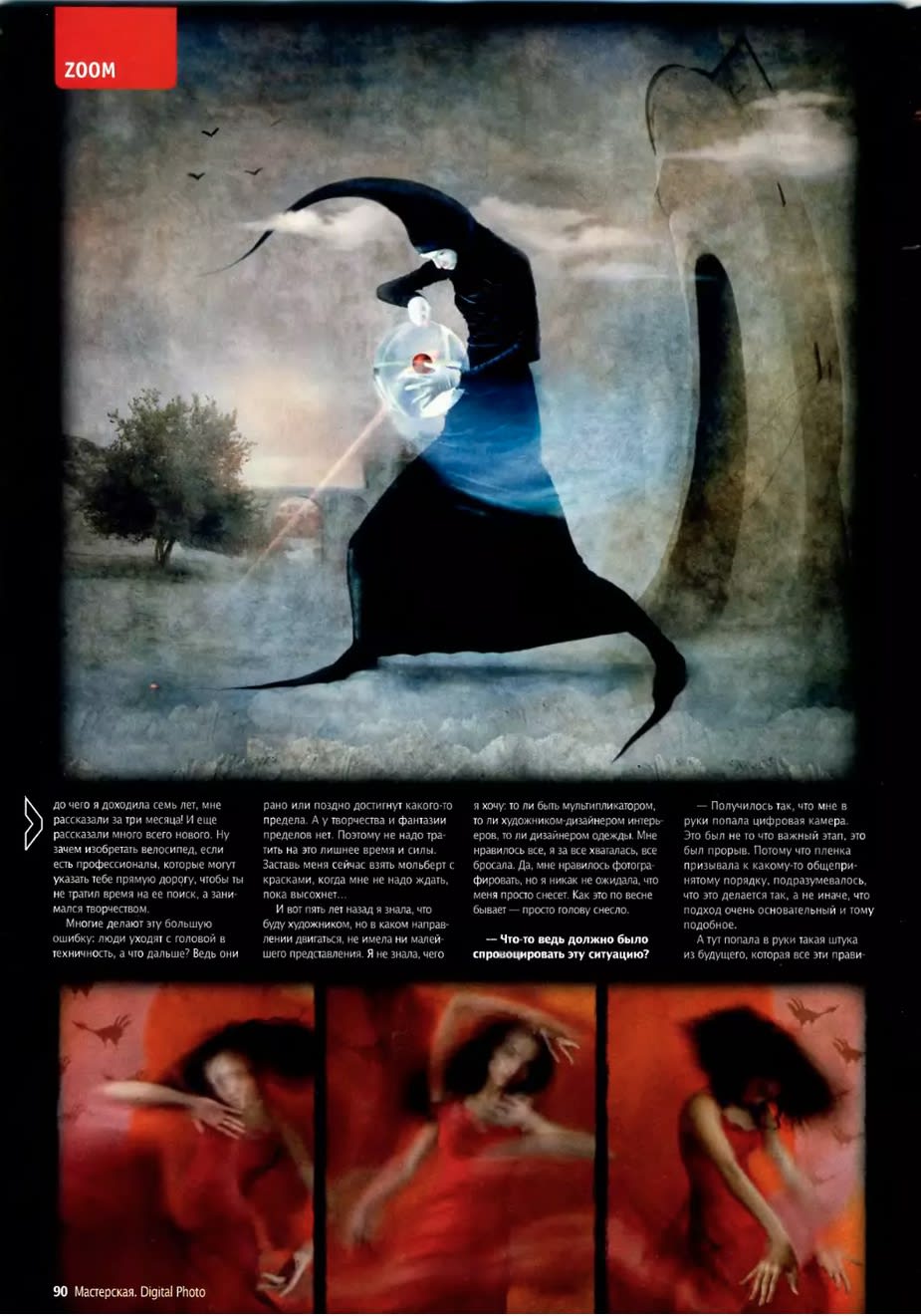

The first time we met Katya was at the birthday party of "Photosite." It took place in a wonderful bar that allowed you to move from a large, noisy hall into a dark room with wooden tables and then drift into another space with a large white screen, where countless "photos of the day" would appear and fade away.

It was a mysterious place—a place where people materialized, people who had previously existed only as nicknames, comments, and photographs. Those passing by whispered conspiratorially about having seen Lisin, Shanidze, and other well-known figures.

However, the enigmatic mention of Belkina, who was supposedly also attending the event, made my imagination work hard to visualize this person I had never seen before. Whether under the influence of the artist’s works or the unusual atmosphere, my mind began to conjure up silly, extravagant pigtails and striped stockings…

How surprised I was when those very striped stockings emerged from the projector room—the place where, judging by the gathering, only the most devoted members of the Photosite community were seated.

I wanted to greet the newly materialized Belkina and walked toward her, trying to come up with an unconventional greeting on the spot. And I might have succeeded—if not for our mutual acquaintance, Yegor Pechnikov, known as Spooner (remember, he was one of the first featured in this column!). At that very moment, he tugged on my sleeve, pointed in an entirely different direction, and said, "And here is Katya Belkina."

To my surprise—and sincere delight—Katya turned out to be nothing like I had imagined. She was both calm and cheerful at the same time, very feminine, and from the few words we exchanged, it was clear that talking to her was easy and natural—without any unnecessary extravagance.

More than a year has passed since then—a year in which we have grown a little and introduced you to many remarkable photographers and artists.

It just so happened that among all these talented people, there wasn’t a single professional artist—someone for whom creating beautiful images was not just a hobby but a real job. At least, that was the main reason we decided to invite Katerina Belkina as our guest.

When she walked into a Moscow café where we had arranged to meet, it became clear that we hadn’t chosen her for any specific reason—we had simply invited her because Katya is like spring itself, and it would have been strange if she weren’t featured in our spring issue.

Katya, you know, before the interview, I went online, typed in your name, and immediately came across this phrase: "When I grow up, I want to be Katerina Belkina." How would you comment on that?

Katya smiled, unable to hide her emotions, and said, "That’s amazing!"

Do you hear that kind of thing often?

Quite frequently!

And does it ever make you uncomfortable?

No, it affects everyone differently, but for me, it’s a positive thing. It doesn’t make me complacent. On the contrary, if there’s no interaction with the world, no validation of what I do, that actually slows me down. I want to bring joy, and enthusiasm is proof that there’s something meaningful in my work.

Do you have students?

Oh, no, I’m not ready for that yet. Of course, I’ve worked with children, but teaching adults is a completely different matter.

Where are you working now?

Nowhere. I’m independent, a free person, not someone’s court artist. My husband, Alexey Lebedinsky, and I have done work for Afisha, Porsche, Lukoil-Neva, and other major projects. I handle many things through an agency to minimize direct interaction with clients.

Why?

They really want to be involved, but in the end, they don’t fully understand what they want. Few people are willing to hand over creative control. But I can’t spend my time convincing clients—that’s not my job. It drains my energy and kills my inspiration.

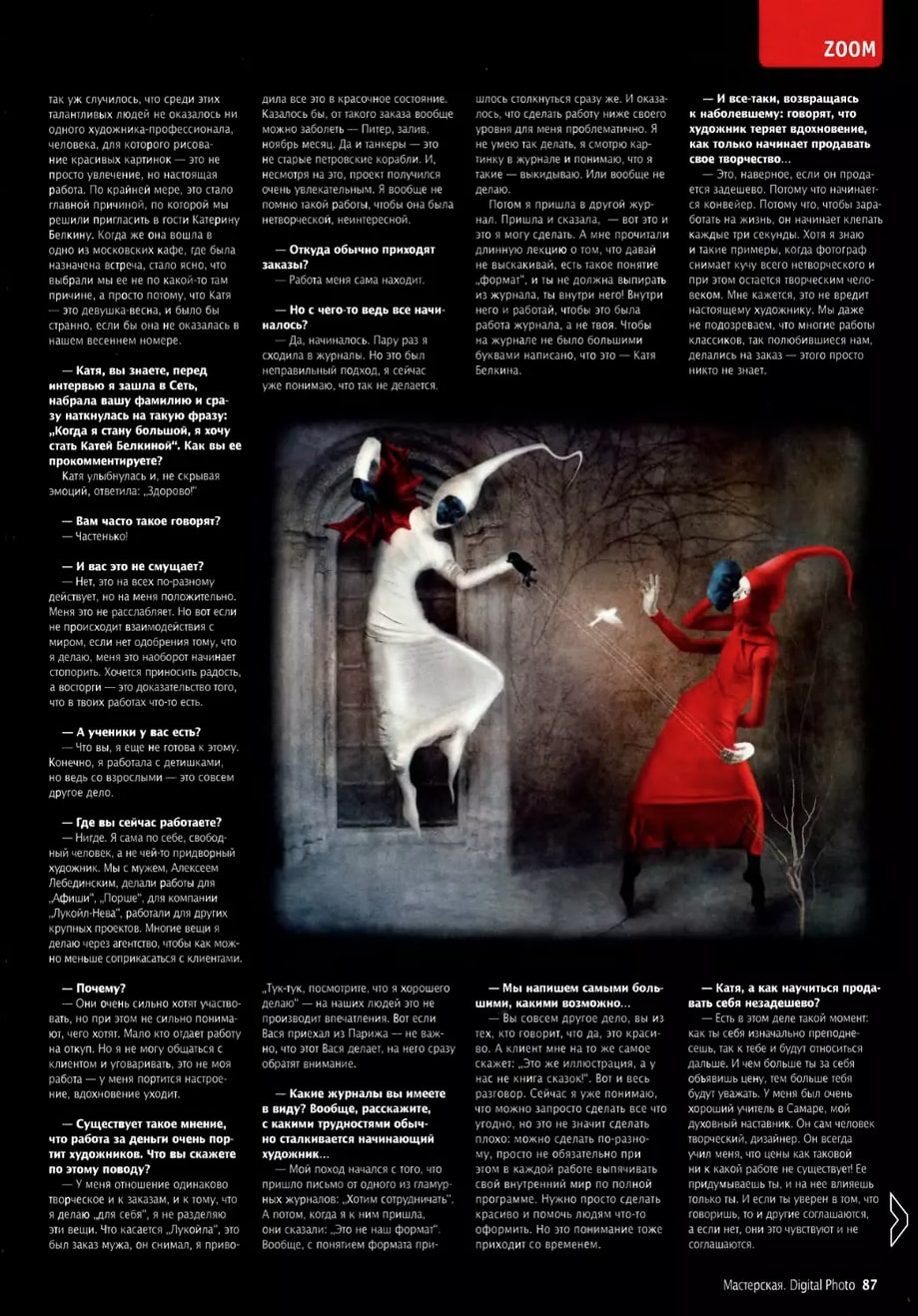

There’s a belief that working for money ruins artists. What do you think?

I approach commissions and personal work with the same creative mindset—I don’t separate them. Take Lukoil, for example: that was my husband’s project—he did the photography, and I brought it to life in color.

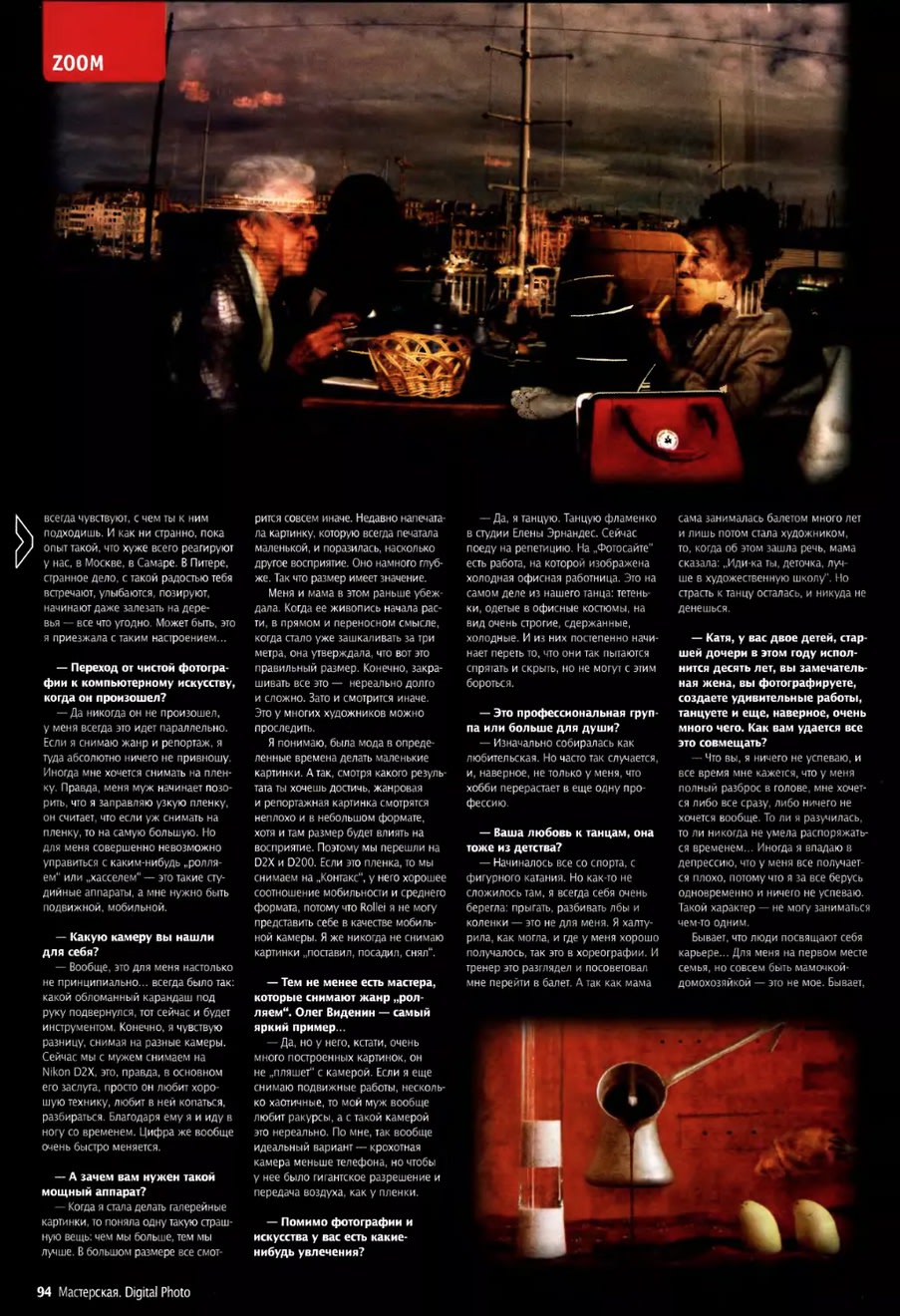

You might think such a job would be dreary—St. Petersburg, the bay, November. And tankers aren’t exactly historic ships from Peter the Great’s era. But despite all that, the project turned out to be incredibly exciting. I honestly can’t recall a single job that felt uninspired or uncreative.

Where do your commissions usually come from?

The work finds me.

But surely, you had to start somewhere?

Of course. A couple of times, I went to magazine offices. But now I realize that’s not how it works. Walking in with a “knock-knock, look at what I can do!” approach doesn’t impress people here. But if Vasya arrives from Paris—doesn’t matter what Vasya does—suddenly, everyone pays attention.

Which magazines are you referring to? And in general, what challenges do young artists typically face?

My journey began when I received an email from a glossy magazine saying, "We’d love to collaborate!"

But when I arrived at their office, they told me, "This isn’t our format."

I had to confront the concept of "format" right away. And I quickly realized that working below my own artistic standard was difficult for me. I simply can’t do it. I look at certain magazine illustrations and think, I would throw that away. Or not even make it in the first place.

Then I visited another magazine. I came in and said, "This is what I can do." And they responded with a long lecture: "Don’t stand out too much. There’s this thing called ‘format,’ and you need to fit inside it. You’re inside the magazine—you work within it. The magazine should be the focus, not you. Your name shouldn’t be plastered all over it in big letters saying, ‘This is Katerina Belkina.’"

Now, I understand that you can do anything you want, but that doesn’t mean you have to force your artistic identity into every piece. Sometimes, it’s about simply making something beautiful and helping people bring their ideas to life. But that kind of understanding comes with experience.

And still, coming back to a common concern: people say that as soon as an artist starts selling their work, they lose their inspiration...

That probably happens if they sell themselves too cheaply. Because then it becomes a conveyor belt. In order to make a living, they start churning out work every three seconds. But I also know photographers who shoot a ton of uninspired material yet still remain true artists. I don’t think it harms a real artist.

We don’t even realize that many works by classic artists—ones we love so much—were created on commission. People just don’t know that.

Katya, how does one learn to sell themselves without underpricing their work?

There’s a simple truth to this: how you present yourself at the beginning determines how people will treat you moving forward. The higher you set your price, the more respect you earn.

I had a great mentor in Samara, my spiritual guide. He was a creative person himself, a designer. He always taught me that there’s no such thing as a fixed price for any piece of work! You invent it, and you control it. And if you believe in the price you set, others will accept it. But if you’re unsure, they will sense it—and they won’t agree.

96

of 96